By Sauntharya Manikandan, J.D. Class of 2027

Introduction

Dark patterns. The phrase itself sounds sinister—perhaps even something out of a Star Wars movie. And while that comparison might seem playful, the reality isn’t far off. The term refers to the types of purposeful deceptive online practices that manipulate users into taking actions. Even though we like to believe we’re in control of our online decisions, dark patterns quietly chip away at that sense of autonomy. From being forced to create an account just to make a purchase to accidentally downloading something by clicking the “X” on a pop-up, these deceptive tactics are everywhere. Coined by user experience designer Harry Brignull, the term “dark pattern” highlights both the unethical nature of these practices and how difficult they are to spot. What began as a concern within the UX design community has since drawn the attention of lawmakers and consumer advocates, as awareness grows of just how much influence these dark patterns wield in our digital lives.

So what exactly does a dark pattern look like? The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) conducted a detailed report in 2022 that highlighted four main categories of dark patterns as designs and features that: create false belief, conceal important information, lead to unauthorized charges, or obscure or manipulate privacy choices. And many of the categories are not exclusive to each other—rather, they are used in combination to lead to a more injurious impact.

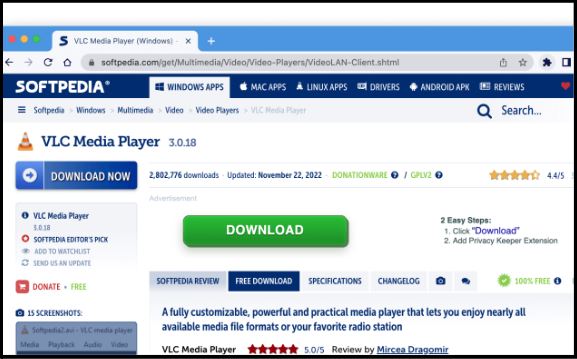

In dissecting Softpedia’s webpage below, we can see these categories of dark patterns at play.

- The bright green download button would create the false belief to a user that clicking on this button would download the desired software.

- By concealing the important information that the ad is separate from the website interface, the user is led to download a privacy keeper extension that would likely manipulate their privacy choice.

Current Regulation and Litigation

As these various types of dark patterns become ubiquitous, regulators at both the state and the federal level are attempting to increase their enforcement efforts against dark patterns. At the federal level, dark patterns are regulated primarily by the Federal Trade Commission under Section 5 of the FTC Act, which explicitly prohibits “unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce.”

However, there are criticisms of whether this level of statutory authority is sufficient to curb the use of dark patterns. Some critics believe the statute is not being used to its full potential, as the FTC rarely brings suits under the unfairness prong. This reluctance to use the unfairness prong is due to both accusations of applying the unfairness standard broadly in the past and the high standard for proving something is unfair. Beyond the statute, critics also disagree with the type of rules being used to regulate these dark patterns. Most federal regulation is currently prescriptive, offering specific bans on what an entity can and cannot do. However, these types of regulations fail to keep up with the rapid development of dark patterns and place the burden on consumers to prove intent. Professor Lauren E. Willis, instead, argues for implementing performance-based regulations that require companies to evaluate the effect of their user design against performance objectives set by regulators. Not only does this approach allow for adaptability to new technologies, but it also shifts the burden to the companies accountable for the effects their interfaces have on users.

Despite these criticisms, several successful high-profile cases have been brought under the FTC’s authority. In September 2025, the FTC secured a record-breaking 2.5 billion settlement against Amazon on allegations that Amazon used deceptive dark patterns to sign up consumers for a Prime subscription and later made it difficult to cancel. The FTC’s complaint detailed that customers were repeatedly asked to enroll in Prime during the checkout process, but the option to opt out was obscured. In addition to this subscription tactic, Amazon also implemented what was internally referred to as the Iliad Flow, a four-page, six-click, 15-option process to cancel a subscription. In addition to this settlement, the court imposed injunctive relief on Amazon to: simplify the prime subscription process, provide a clear button to decline subscription, enhance pricing and renewal terms during enrollment, and retain a third party monitor for compliance. One of the points to note in Amazon’s response was that the FTC was unconstitutionally attempting to enforce a prohibition on dark patterns that did not exist under its current authority. And while there is no clear law banning dark patterns, expert Andrea Matwyshyn explains the statutory authority is “intentionally broad so the FTC can regulate whatever the technology and business practices of the moment are.”

Still, this recurring pushback from defendants—and growing concerns about consumer autonomy—has spurred momentum for additional protections at the state level. Over twenty states have imposed additional requirements on data collection, use, and disclosure. These laws differ widely in scope and enforcement and do not all explicitly target dark patterns; but many still operate to discourage manipulative design by reinforcing requirements for clear consent, notice, and transparency. Of these, California has served as the forerunner through the implementation of the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA). While the CCPA grants users more autonomy over their data, the CPRA provides a specific definition of dark patterns and finds agreements obtained through the use of dark patterns as non-consensual. In direct response to the issue of automatic subscription like in FTC v. Amazon, California also enacted the Click-to-Cancel Renewal law, requiring businesses to make it as easy to cancel as it is to sign up.

The Future of Dark Patterns and Reimagining User Autonomy

As we consider the future of dark pattern regulation, it becomes increasingly apparent how much of our internet economy thrives on the ability to not only access user data but also use it to manipulate user actions. Traditional ideas about competition and pricing regulating markets do not fit these data economies. In these data markets, consumers pay with their personal information—often without any understanding of its true costs.

Scholars have stressed that while state and federal regulations can start to address these issues, the societal and cultural expectations we have around data need to be considered as well. In efforts to return user autonomy, Eric Posner and Glen Weyl advocate for the creation of a data labor union, where consumers receive compensation for sharing the personal data that is, in turn, utilized by businesses. Professor Aziz Z. Huq offers another solution under the common law doctrine of public trust, where data is treated as a state managed asset for the collective interest. Ultimately, without a fundamental rethinking of how data, consent, and autonomy intersect in the digital marketplace, regulatory efforts will continue to lag behind the evolving tactics of dark patterns that define our online economy.